To my favorite group of humans on the planet, this blog post is a little different because it exists just to tell you about my new favorite thing I’ve made: The Fuckit Bucket™.

Tee hee hee.

The Fuckit Bucket™ was born out of sheer delight. A friend of mine, embroiled in the world of C list celebrity and a nasty split from her baby daddy, was talking about how her life was so screwy that she was running out of fucks to give. I suggested that she put all the fucks in a bucket for rationing. A “Bucket ‘o Fucks” we called it. I even made a prototype:

I thought, everyone should have their own bucket. For two years, the Bucket ‘o Fucks noodled in my mind. I giggled every time I thought about it, and wanted to make a talisman of sorts to keep me giggling day to day. And then, sometime between 2016 and 2018, I heard the phrase, “Chuck it in the fuck it bucket and move on.” Fuck it bucket had a better ring to it, so I stored the phrase away. I would know when it was time.

In 2019, I caught a headline about how the Supreme Court deemed that swear words were, in fact, a form of free speech. The US Trademark and Patent Office would no longer be allowed to reject applications with swearing or immoral words or symbols. I searched “Fuck it bucket” on the USPTO website, and found that the phrase had not been trademarked. It was time to create.

As a former small business owner and small business lover, I did not want to produce the bucket overseas, even in exchange for a lower bottom line. After designing my little bucket, I found a smelter in upstate New York to cast the product. While he was pouring molten metal into my design, I went to work on trademarking. I figured that best case scenario, people would get a giggle out of the Fuckit Bucket™ like I do and snag them up on Etsy. Worst case, I wouldn’t sell a single bucket but I’d never have to buy anyone a Christmas or birthday present again.

Turns out, people love it. I launched the Fuckit Bucket™ just last week, as a response to the train wreck presidential debate. This year continues to pound down, and I decided it was time to bring a little levity back to the dog & pony show that is 2020. And given that we still have two more debates, an election, and the holidays coming up…well, everyone is going to need their own Fuckit Bucket™.

Buckets are available on a necklace, keychain, or as a stand-alone charm.

We’ll be back to our regularly scheduled programming soon, folks. After so many years of depression, I am basking in the fact that I can find so much joy in creating a silly little bucket. This is why we do the work. Because when we clear out all the emotional crap, we make room for creation and laughter to come in, which results in both art and delight!

More articles from the blog

see all articles

July 9, 2025

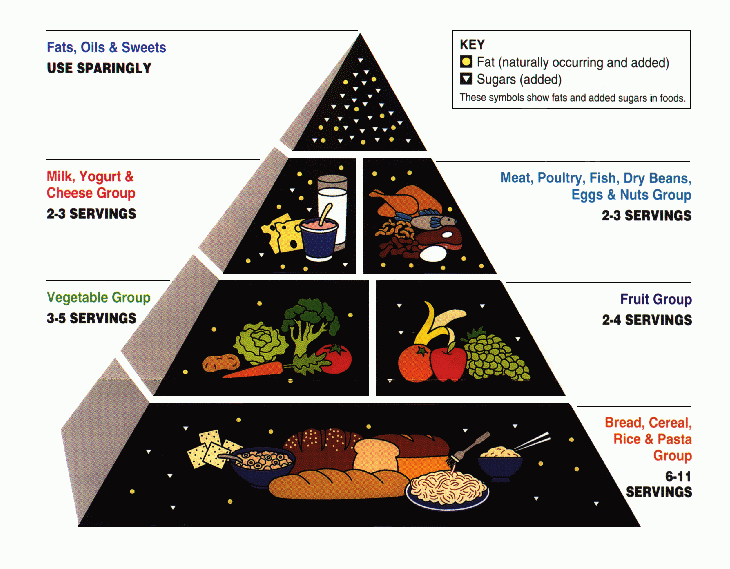

How World War II, cigarette companies, and an obscure 1937 law determine what you put in your mouth today: A Short History of the Sad, Modern American Diet.

read the article

July 2, 2025

“What do all fat, sick, unhealthy people have in common? At least this: they all eat.: An introduction to a new series about diet, psychiatric drug withdrawal, and performance.

read the article

June 25, 2025

Bad Medicine, Antidepressant Withdrawal, and the Incalculable Costs of Medicating Normal: My full talk at the University of Nevada, Reno Medical School

read the article

June 18, 2025