It’s the 100th issue of Happiness Is A Skill, and I’m marking the occasion by going down a rabbit hole of genetic testing through GeneSight. This isn’t your usual, turns out I’m 1% Korean type of genetic testing (true story). It’s relatively new science that analyzes the body’s ability to process psychiatric drugs through the cytochrome P450 system (CYP), a group of enzymes responsible for metabolizing many medications and other substances in the body.

Though I personally have zero plans to ever swallow a psychiatric drug again, the more time I spend in the world of antidepressant withdrawal, the more interested I am in the why of it all. Why is it that some people have no issue stopping psychotropic drugs cold-turkey, while other people, like the man I wrote about in Issue 99, have permanent brain damage from psychiatric drug use and withdrawal?

My hunch is that it has something to do with genetics and the CYP system. Though there are no known studies on the CYP system and withdrawal specifically, there is some emerging research on CYP system and medication side effects. My assumption is that if the CYP system affects how a daily dose of drugs is metabolized, it’s likely involved in clearing the drug out of the system even when a daily dose is no longer being taken.

Hopefully we’re not too far from formal research on the subject, but in the meantime, I’m going to share what I’ve learned about this genetic testing and my results.

What we know so far about the CYP system and its relationship to psychiatric drugs:

The CYP450 pathway is a group of enzymes found in the liver that are responsible for the metabolism of a wide variety of drugs, including antidepressants and antipsychotics. Specifically, the CYP450 enzymes are involved in the breakdown of these drugs in the liver, which can affect their efficacy and potential side effects.

Most antidepressants are metabolized by the CYP450 enzymes through variant alleles (versions) of the CYP450 pathways. For example, allele CYP2C19 is primarily responsible for metabolizing citalopram/Celexa and escitalopram/Lexapro while allele CYP2D6 is primarily responsible for fluoxetine/Prozac, paroxetine/Paxil, and venlafaxine/Effexor.

By looking at the genetic variations in these alleles, we can see how the body metabolizes psychiatric drugs via the CYP450 pathway. Everyone falls into one of the following categories: extensive (normal) metabolizer, intermediate metabolizer, poor metabolizer, rapid or ultra-rapid metabolizer.

An extensive metabolizer is a person with normal enzyme activity levels, meaning they can metabolize drugs normally, and therefore require standard doses of medications.

In contrast, an intermediate metabolizer has reduced activity levels of the CYP enzyme, which means they metabolize drugs slower than expected. As a result, intermediate metabolizers may experience higher overall drug levels or longer exposure to drugs, which can lead to increased risk of side effects or toxicity.

Poor metabolizers have significantly reduced or absent activity of a specific CYP enzyme, which leads to impaired drug metabolism. As a result, poor metabolizers may need to avoid certain drugs altogether due to the risk of adverse effects.

Conversely, ultra rapid metabolizers are individuals with increased activity levels of CYP enzymes, which means they metabolize drugs faster than expected, potentially leading to lower overall drug levels and reduced or absent effectiveness of medications.

Extreme examples of why the CYP system is relevant for both prescribers and patients:

The work of Selma Eikelenboom-Schieveld, a Dutch forensic scientist based out of New Mexico, focuses on the association between genetic variants of the CYP450 enzymes and violence-related adverse drug reactions in patients receiving psychoactive medication.

In her 2016 research paper “Psychoactive Medication, Violence, and Variant Alleles for Cytochrome P450 Genes,” Eikelenboom-Schieveld compared 55 violent individuals—whose behavior ranged from an altered emotional state (30 subjects), to assault, attempted or completed suicide and homicide (25 subjects)—against 58 persons with no history of violence as the controls.

In the nonviolent group, 38 subjects did not use prescription medication. In the violent group, all the subjects were on prescription medication. Of the 75 subjects on medication, 52 (almost 70%) were on three or more medications.

Her research showed that there is an “association between prescription drugs, most notably antidepressants and other psychoactive medication; having variant alleles for CYP2B6, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4; and the occurrence of an altered emotional state or acts of violence. Based on these results, genotyping patients for these six CYP450s would provide information as to who might be susceptible to adverse drug reactions, e.g., the development of an altered emotional state or assault/suicide/homicide.”

To say it another way: if someone is a normal metabolizer or has limited CYP gene variations and is only on one medication, chances are acts of violence are also limited. But in someone with many variants and many medications, the enzymatic pathway effectively gets clogged up, causing a buildup of drugs in the system that can lead to an altered emotional state or violence. These undesirable actions are often mistaken for mental illness, so more drugs added, increasing the likelihood of violence.

More articles from the blog

see all articles

July 9, 2025

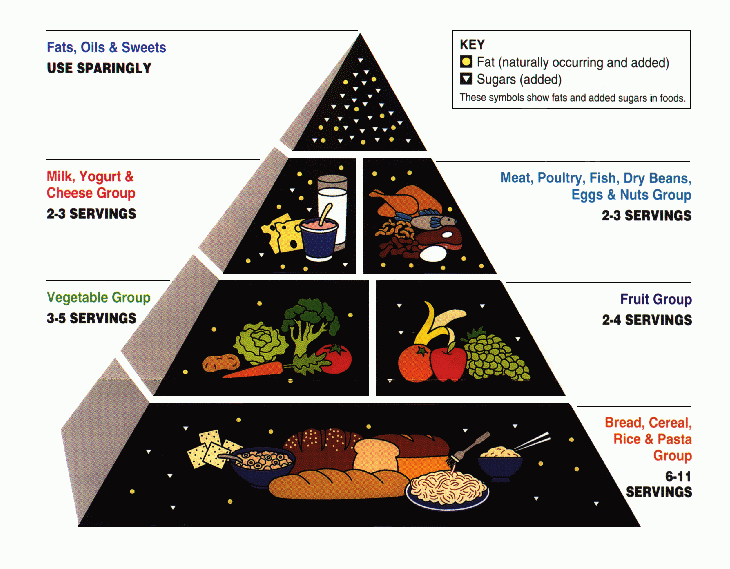

How World War II, cigarette companies, and an obscure 1937 law determine what you put in your mouth today: A Short History of the Sad, Modern American Diet.

read the article

July 2, 2025

“What do all fat, sick, unhealthy people have in common? At least this: they all eat.: An introduction to a new series about diet, psychiatric drug withdrawal, and performance.

read the article

June 25, 2025

Bad Medicine, Antidepressant Withdrawal, and the Incalculable Costs of Medicating Normal: My full talk at the University of Nevada, Reno Medical School

read the article

June 18, 2025